"We don't hide our space program. We do it all up front and in public. That's the way freedom is, and we wouldn't change it for a minute."

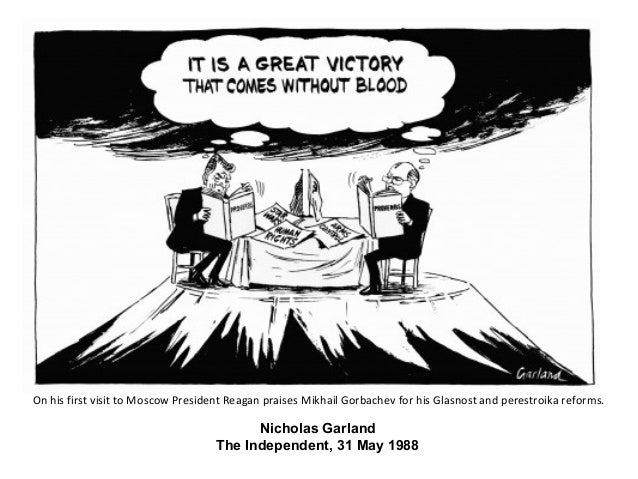

The "open" US v. the "closed" USSR narrative enabled lots of lazy journalism and scholarship during the cold war. When Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1985-1991 period pursued his policies of "perestroika" (restructuring) and "glasnost" (openness), his efforts were almost universally framed in mainstream Western media as the Soviets finally making efforts to become more like the United States. Even though the United States had never come fully to terms with its own history of slavery, Jim Crow, and subjugation of native populations, Gorbachev's attempt to be more open and honest about the historical failures of the Communist bureaucracy and brutality of prior regimes was framed as somehow representing the USSR engaging in an American style search for truth.

Gorbachev's reforms could and should have provoked needed restructuring and greater openness over here. Instead, a great majority of American government leaders and journalists adopted a "triumphalist" narrative in which Gorbachev's program was interpreted as "we won and they lost" the cold war.

After Boris Yeltsin dissolved the Soviet Union in 1991 (and ended up dissolving the Russian parliament by force in 1993) the triumphalist narrative in the West got even louder. Gorbachev's (at least stated) vision of democratic reforms and a people-centered economy gave way to austere, so-called "neoliberal" measures that by the late 1990s had many citizens in Russia and former Soviet states longing for the "old days." The West meanwhile pursued its own brand of neoliberalism which, it is fair to say, by 2008 had significantly wrecked the economy. In 2009 historian Andrew Bacevich I believe was right on point:

"Post–cold war triumphalism produced consequences that are nothing less than disastrous. Historians will remember the past two decades not as a unipolar moment, but as an interval in which America succumbed to excessive self-regard. That moment is now ending with our economy in shambles and our country facing the prospect of permanent war."

Bacevich thought he was writing a postmortem for triumphalism. Obviously he was being too optimistic, as the Obama years offered no significant challenge to the narrative. Indeed, the political establishment's current stance toward Russia--which has even liberals like Rachel Maddow participating in a kind of neo-McCarthyite hysteria--appears to be rooted almost entirely in triumphalism. (Which is in NO WAY a defense of the alleged and/or real corruption and thuggery of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. In fact it is the triumphalist narrative that is in large part responsible for producing "democratators" like them.).

I thought about all this recently while watching the controversy play out over the removal of Confederate statues in many part of the south and even in some northern locations. Because we've never had a period of glasnost in the United States, most people seem to have no idea why and how Confederate statues got put where they are in the first place. Will the tragic death of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, killed as she protested a white supremacist rally, force journalists, government officials, and school curriculum directors to rethink our history?

We are seeing some movement in that direction. Even before the death of Ms. Heyer, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu courageously defended the removal of confederate statues from the city: "They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments celebrate a fictional, sanitized confederacy ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, ignoring the terror that it actually stood for. They may have been warriors, but in this cause they were not patriots."

Actions by local officials like Mayor Landrieu--along with the opening for debate and discussion provided by Charlottesville tragedy--allows for greater dissemination of accurate information about our past. Finally there is media interest in items such as data provided by the Southern Poverty Law Center. SPLC researchers found that:

*There are at least 1,503 symbols of the Confederacy in public places.

*There are at least 109 public schools named after prominent Confederates, many with large African-American student populations.

*There are more than 700 Confederate monuments and statues on public property throughout the country, the vast majority in the South.

*There were two major periods in which the dedication of Confederate monuments and other symbols spiked--the first two decades of the twentieth century and during the civil rights movement.

*The Confederate flag maintains a publicly supported presence in at least six southern states.

*There are 10 major US military bases named in honor of Confederate military leaders.

*There have been at least 100 attempts at the state and local levels to remove or alter publicly supported symbols of the Confederacy.

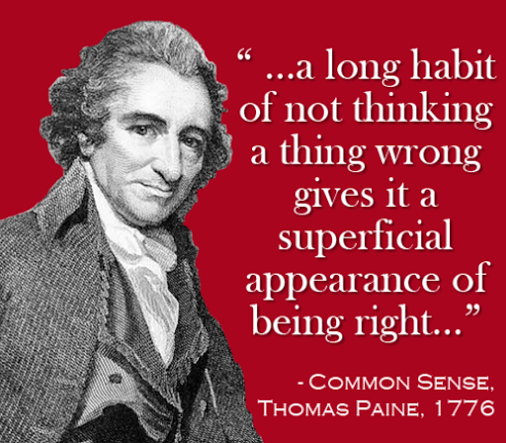

In the wake of Charlottesville, many pundits and government officials are grappling with coming to terms with the Confederacy and white supremacy. This process, in my view, represents an American glasnost that will be painful and controversial. Because we've never had a real period of glasnost, those choosing to challenge white supremacist symbols (and really all forms of white supremacy) need to be prepared to confront the many rationalizations, delusions, sweeping under the rug, and outright dishonesty that appear any time a society is in a period of change. The American revolutionary Thomas Paine's explanation for these kinds of mental gymnastics in defense of tradition I think is still the most clear and concise: "a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom."

Think about that Sam Adams quote next time you find yourself engaged in a discussion with someone who sees Confederate symbols as "no big deal," "just history," "heritage," and yada yada yada.

The breakdown of the Soviet Union in 1991 presented the United States with a golden opportunity to reflect on its own historic failures to live up to its Constitutional ideals. We blew the opportunity and instead were guided by a triumphalist narrative that made it easy to sweep difficult conversations and overt injustices under the rug.

Some will call the effort to come to terms with the Confederacy and other uncomfortable parts of American history the work of radicals and malcontents. I call it inching toward glasnost--American style.