Welcome To Tony Palmeri's Media Rants! I am a professor of Communication Studies at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. I use this blog to try to promote critical thinking about mainstream media, establishment politics, and popular culture.

Thursday, June 24, 2010

I'll be on Friday's "Week in Review"

I'll be on Friday's WPR Week in Review tomorrow (June 25) opposite former WI state senator and Lieutenant Governor Margaret Farrow. Gene Purcell will be hosting the show in place of Joy Cardin. You can call in live at 1-800-642-1234 or email talk@wpr.org

Friday, June 04, 2010

Jim Joyce's Lessons For Politicians

By now everyone knows that umpire Jim Joyce's blown call cost the Tigers' Armando Galarraga a perfect game. Umpire Joyce's recognition of his error has earned him praise from Mr. Krause and many others.

They/we probably won't, but politicians can learn two important lessons from the Joyce Affair.

Lesson Number One: Don't Pander; Call 'em as you see 'em: Joyce's blown call occurred with two outs in the top of the 9th inning, in Galarraga's home park, with the crowd cheerleading for the perfect game. Especially on such a close play, the easiest thing for Joyce to do would have been to call the runner out even if his eyes and heart told him the runner was safe. Instead of pandering to the crowd, he called the play as he saw it and suffered the immediate consequences.

Contrast that behavior with the norm in contemporary American politics. Pandering to cheerleaders--who are frequently well connected insiders with a vested interest in the outcome of policy deliberations--is the way the game is too often played. (That's essentially Madison and Washington politics in a nutshell.).

No one should be surprised that pandering to the powerful is the norm in Madison and Washington, but one of my biggest wake-up calls since getting on the City Council has been the extent to which that dynamic plays out locally too. Just raising questions about Oshkosh Corporation, EAA, and other entities backed up by well connected cheerleaders is extremely difficult.

Lesson Number Two: Evidence Matters. What's significant about Joyce's change of mind on the call is not just that he admitted error, but that he changed his mind after being confronted with contrary evidence. Even though the video evidence seemed pretty conclusive, Joyce could have easily said something like, "the video is misleading; if you'd been standing where I was you would have agreed that the runner got there first." Instead of spinning and rationalizing, Joyce accepted that the video evidence suggested that the runner was probably out.

Contrast that with the "dumbassification" that we see in American politics. Facts and evidence often mean nothing, especially if they get in the way of a good smear or a catchy, poll-tested slogan. (Probably the best current example of this phenomenon is the repeated attempts by Obama's opponents to label him a "Socialist" in spite of the fact that his economic policies were developed by Wall St. insiders and outfits like Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase have been among his biggest contributors.).

American politicians tend to change positions not because further study reveals powerful counter evidence, but because of some need to pander to a cheerleader perceived as powerful. That's why we justifiably refer to position-changing pols as "flip-floppers."

Integrity means not only the willingness to take heat for a controversial stand, but also the courage to change course when contrary evidence emerges. Jim Joyce showed that kind of integrity. How sad that the modern Democratic and Republican parties have no room for that kind of individual.

They/we probably won't, but politicians can learn two important lessons from the Joyce Affair.

Lesson Number One: Don't Pander; Call 'em as you see 'em: Joyce's blown call occurred with two outs in the top of the 9th inning, in Galarraga's home park, with the crowd cheerleading for the perfect game. Especially on such a close play, the easiest thing for Joyce to do would have been to call the runner out even if his eyes and heart told him the runner was safe. Instead of pandering to the crowd, he called the play as he saw it and suffered the immediate consequences.

Contrast that behavior with the norm in contemporary American politics. Pandering to cheerleaders--who are frequently well connected insiders with a vested interest in the outcome of policy deliberations--is the way the game is too often played. (That's essentially Madison and Washington politics in a nutshell.).

No one should be surprised that pandering to the powerful is the norm in Madison and Washington, but one of my biggest wake-up calls since getting on the City Council has been the extent to which that dynamic plays out locally too. Just raising questions about Oshkosh Corporation, EAA, and other entities backed up by well connected cheerleaders is extremely difficult.

Lesson Number Two: Evidence Matters. What's significant about Joyce's change of mind on the call is not just that he admitted error, but that he changed his mind after being confronted with contrary evidence. Even though the video evidence seemed pretty conclusive, Joyce could have easily said something like, "the video is misleading; if you'd been standing where I was you would have agreed that the runner got there first." Instead of spinning and rationalizing, Joyce accepted that the video evidence suggested that the runner was probably out.

Contrast that with the "dumbassification" that we see in American politics. Facts and evidence often mean nothing, especially if they get in the way of a good smear or a catchy, poll-tested slogan. (Probably the best current example of this phenomenon is the repeated attempts by Obama's opponents to label him a "Socialist" in spite of the fact that his economic policies were developed by Wall St. insiders and outfits like Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase have been among his biggest contributors.).

American politicians tend to change positions not because further study reveals powerful counter evidence, but because of some need to pander to a cheerleader perceived as powerful. That's why we justifiably refer to position-changing pols as "flip-floppers."

Integrity means not only the willingness to take heat for a controversial stand, but also the courage to change course when contrary evidence emerges. Jim Joyce showed that kind of integrity. How sad that the modern Democratic and Republican parties have no room for that kind of individual.

Tuesday, June 01, 2010

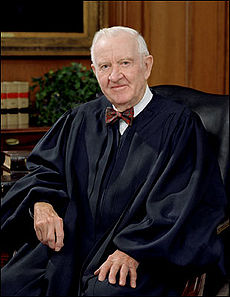

Media Rants: Justice Stevens' Uneven First Amendment Legacy

Update July 17, 2019: Yesterday Justice John Paul Stevens passed away at the age of 99. I wrote this piece in June of 2010, shortly after Stevens retired from the Supreme Court. Justice Stevens continued to have an impact on legal thinking after he left the Court, including what I believe to be a persuasive argument for repealing the Second Amendment. We should never forget that Justice Stevens, who the popular press insisted on calling "liberal" but was in fact a fierce independent, was appointed by a Republican president (Gerald Ford) who understood the terrible impact on representative democracy and the rule of law when judges were perceived as partisan hacks. Today it is virtually impossible to imagine someone like Stevens appointed by a Republican president. --Tony Palmeri

Update July 17, 2019: Yesterday Justice John Paul Stevens passed away at the age of 99. I wrote this piece in June of 2010, shortly after Stevens retired from the Supreme Court. Justice Stevens continued to have an impact on legal thinking after he left the Court, including what I believe to be a persuasive argument for repealing the Second Amendment. We should never forget that Justice Stevens, who the popular press insisted on calling "liberal" but was in fact a fierce independent, was appointed by a Republican president (Gerald Ford) who understood the terrible impact on representative democracy and the rule of law when judges were perceived as partisan hacks. Today it is virtually impossible to imagine someone like Stevens appointed by a Republican president. --Tony PalmeriJustice Stevens’ Uneven First Amendment Legacy

Media Rants

By Tony Palmeri

From the June 2010 issue of The SCENE

Disgust with the Supreme Court’s rightist RATS (Roberts, Alito, Thomas, Scalia) often leads leftish legal pundits to exaggerate the accomplishments of the Court’s so-called liberal bloc.

Nowhere is this tendency clearer than in the reactions to Justice John Paul Stevens’ retirement announcement. Senator Dick Durbin’s (D-IL) comments were typical: ''Justice Stevens' commitment to expanding freedom, safeguarding our rights and liberties, and understanding the challenges faced by ordinary Americans will be his legal legacy. He has had no judicial agenda other than fidelity to the law and the Constitution."

Appointed by President Ford in 1975, Stevens labeled himself a “centrist” and early in his term authored conservative opinions on affirmative action, the death penalty, and other hot button issues. His views on the death penalty and coercive state power in general evolved over time, so that by the 1990s media depictions almost unanimously recognized him as the Court’s liberal leader. Indeed, Stevens deserves kudos for being a voice of reason against Bush-era executive branch excesses in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006).

Disgust with the Supreme Court’s rightist RATS (Roberts, Alito, Thomas, Scalia) often leads leftish legal pundits to exaggerate the accomplishments of the Court’s so-called liberal bloc.

Nowhere is this tendency clearer than in the reactions to Justice John Paul Stevens’ retirement announcement. Senator Dick Durbin’s (D-IL) comments were typical: ''Justice Stevens' commitment to expanding freedom, safeguarding our rights and liberties, and understanding the challenges faced by ordinary Americans will be his legal legacy. He has had no judicial agenda other than fidelity to the law and the Constitution."

Appointed by President Ford in 1975, Stevens labeled himself a “centrist” and early in his term authored conservative opinions on affirmative action, the death penalty, and other hot button issues. His views on the death penalty and coercive state power in general evolved over time, so that by the 1990s media depictions almost unanimously recognized him as the Court’s liberal leader. Indeed, Stevens deserves kudos for being a voice of reason against Bush-era executive branch excesses in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006).

As regards freedom of speech and the First Amendment, Stevens’ legacy is mixed. I believe his passionate and superbly argued dissenting opinion in the recent Citizens United v. FEC case will in future years have an impact not typical of minority opinions. In that case, the RATS were joined by Justice Anthony Kennedy in outlawing virtually all restrictions on corporate involvement in elections. Wrote Stevens: “The Court’s ruling threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the Nation. The path it has taken to reach its outcome will, I fear, do damage to this institution.”

Even more powerfully, Stevens dissent featured a rare example of a judge questioning the “personhood” of corporations:

“The fact that corporations are different from human beings might seem to need no elaboration, except that the majority opinion almost completely elides it . . . It might also be added that corporations have no consciences, no beliefs, no feelings, no thoughts, no desires. Corporations help structure and facilitate the activities of human beings, to be sure, and their ‘personhood’ often serves as a useful legal fiction. But they are not themselves members of ‘We the People’ by whom and for whom our Constitution was established.”

Should the Supreme Court ever break free of its dominant RATS/moderates coalition, Stevens’ cogent understanding of the nature of corporations might serve as a foundation on which to reclaim the Constitution for “We the People.”

Stevens First Amendment contribution with the most practical and positive impact is probably his majority opinion in Sony Corporation of America v. Universal City Studios (1984). In that case, a court majority led by Stevens rebuffed Hollywood’s attempt to outlaw video tape recorders on the grounds that they could be used for copyright infringement. In a victory for consumers, Stevens wrote: "the sale of copying equipment...does not constitute contributory infringement if the product is widely used for legitimate, unobjectionable purposes, or, indeed, is merely capable of substantial noninfringing uses."

Unfortunately Stevens did not apply the same logic in MGM Studios v. Grokster (2005), joining the majority in refusing to apply the Sony standard to file sharing technology. Holding narrowly that file sharing technology was legitimate but that Grokster’s “crime” was in encouraging copyright infringement, the Court guaranteed only that entertainment companies would continue to use the courts to stifle what they perceive as illegal downloading. The result? Tens of thousands of lawsuits filed against music fans, against everyone from teen students to grandmothers.

Stevens’ two worst First Amendment opinions dealt with flag desecration and “indecent” media, respectively. In Texas v. Johnson (1989), Stevens was one of four justices disagreeing with the majority opinion that flag desecration constituted expression worthy of First Amendment protection. In a dissent that sounded more like Archie Bunker than a great civil libertarian, Stevens insisted that requiring he who desires to burn a flag use an alternative method for expressing his ideas is a “trivial burden” on free expression.

Stevens’ First Amendment opinion with the most negative impact can be found in Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation (1978). The case dealt with the FCC’s power to prevent broadcasters from airing “indecent” material such as George Carlin’s famous “Filthy Words” monologue. Writing for the majority, Stevens insisted that the pervasiveness of mass media, along with government’s legitimate interest in protecting children, allowed the FCC to restrain the broadcast of “indecent” materials without violating the First Amendment. Thanks to this decision, we’ve now lived through more than thirty years of the FCC in the role of a boorish Big Brother, anxious to level fines at broadcasts featuring penis jokes or anything else deemed “indecent” by bureaucrats and judges.

Justice Brennan’s dissent aptly smacked down the Court majority, finding in Stevens’ opinion “a depressing inability to appreciate that in our land of cultural pluralism, there are many who think, act, and talk differently from the Members of this Court, and who do not share their fragile sensibilities.”

At his best, John Paul Stevens defended the Constitution against government and corporate attempts to bend and subvert it for their own purposes. Should Elena Kagan be confirmed as his replacement, let’s hope she is Stevens 2.0 instead of a RATS clone or Stevens-lite. [Update July 2019: In her recent dissent against the court majority's recent refusal to reign in hyper partisan gerrymandering, Justice Kagan showed signs of being a Stevens 2.0.].